When assessing a potential site, consider the nature of the landscape and what the trees will be exposed to daily in the environment. Trees are often planted based on the average weather conditions, when in actuality, they experience (relative) seasonal extremes of hot and cold.

This section includes information and considerations for assessing a site in order to give trees the best chance at successful development, including planning ahead, soil considerations, light tolerance, branch conflicts, determining a location, root considerations, the potential impact of invasive species, as well as pests and diseases.

1. Planning ahead

To achieve a favourable result in the future, start by creating a plan that will lay out your path to tree planting success. Questions to address could include the following:

- What are the goals of the tree planting? For example: to increase biodiversity, create shelter, mitigate erosion, or provide a food source for wildlife.

- Site condition considerations, such as the following:

- Will the site be exposed to elements such as wind, road salt or pollution?

- Is the soil moist or dry? Acidic or alkaline? Clay or sandy?

- Will sunlight requirements be met?

- How will you determine any currently unknown (to you) site conditions?

- Will the site meet the needs of the tree(s) once they have reached full maturity, including the following:

- Considering the anticipated size and shape of the mature tree

- Spacing needs

- Are there potential environmental impacts on the existing ecosystem? For example: planting dominant species that will choke out existing native populations, or planting trees where an existing ecosystem provides a unique habitat for plants and animals that would be negatively impacted by introducing tree species (e.g., native prairie grassland ecosystems)

2. Soil considerations

The relationship between a tree and the soil where it is planted is complex and has a major influence on a tree’s growth and health. Soils are described by indicators including their physical composition (minerals that make up the soil and how they’re arranged) and chemical composition (acidity, salinity and nutrients).

Soil considerations include access to moisture, nutrients, temperature, drainage and porosity. Try to choose a site that will provide as many of these growth requirements as possible, while also selecting a tree that will grow well in the existing soil. Conditions vary between sites and are not always obvious during a single visit.

Indicators to assess include the following:

Soil structure

- A soil structure with the presence of good pore space allows roots to grow and access air, water and nutrients.

- If poor soil is assessed, its composition can often be improved with the addition of elements such as compost, sand, structural soils, etc. Note: this can create multiple soil profiles for the root system to navigate as the tree grows. Ideally, a tree should be selected to match the site conditions.

Compacted soil

- A simple test for soil compaction and water uptake is to dig a hole, pour water into it and see how quickly it drains out.

- In sites with compacted soil, often less water and air are accessible to the fine roots, and the growing tips have a harder time forcing their way through the material. This is a common problem for urban trees and includes any area that has frequent foot or vehicle traffic.

- Where serious compaction has occurred, a pitchfork can be (carefully) used to loosen the soil in the root zone.

Soil water

- Soil water availability can often be a critical problem for newly established trees. Too little causes drought-like conditions and without an established root system, the seedling will fail. Too much water, and the roots will lack access to oxygen, also leading to seedling failure. This is discussed further in Post-Planting and Establishment.

3. Light tolerance

Trees vary in their response to sunlight levels. Tree species can have a narrow or wide range of light tolerance. Matching the right tree to a specific site location based on light availability will increase its chances for long-term success.

| SUN TYPE | EXPOSURE TO SUNLIGHT |

| Full Sunlight | More than 6 hours of direct sunlight per day |

| Partial Shade | Fewer than 6 hours of direct or filtered sunlight per day |

| Full Shade | Fewer than 4 hours of filtered sunlight per day; very little to no direct sunlight per day |

4. Branch Conflicts

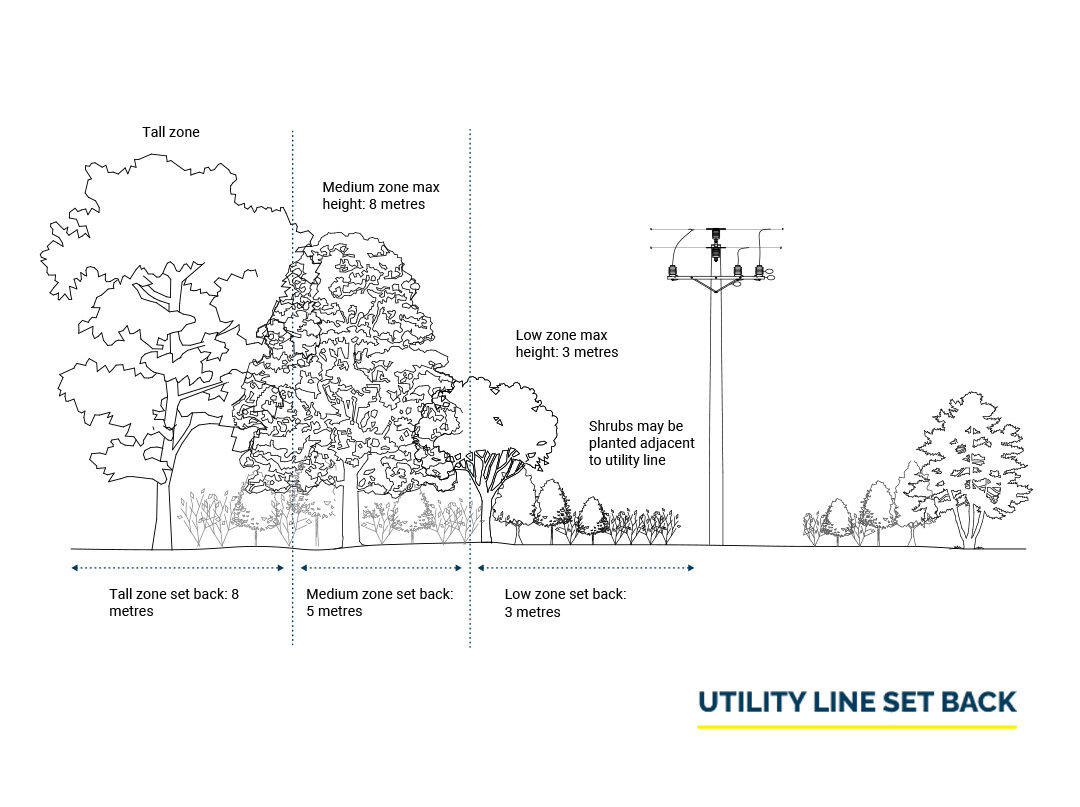

Prior to planting, it is essential to determine the distance from the planting site to nearby infrastructure (trails, buildings, utility wires, poles, bridges, etc.). When choosing species, aim to reduce the chances of branch conflict by considering the mature size (both height and width), growth form or habit in relation to nearby trails or structures.

If you have a question about any established guidelines in your area, check with the relevant local authority.

5. Determining a location

When determining the feasibility of a location for tree planting, several factors should be considered. These include advance research, buffer distance needs, the potential of salt and de-icing damage, and accessibility.

Advance research

Before digging, make sure to be informed about underground utility locations. The local municipality is a good starting point for determining the appropriate people/companies who can provide this information. Once you have received the information, use it to avoid buried cables and wires on the property as you conduct tree-planting activities.

Buffer distances

Riparian buffers are planted to create a buffer zone between agricultural land and bodies of water. Among many benefits, a riparian buffer can help to stabilize eroding banks and protect waterways and farmland. To begin the process:

- Inventory of previous vegetation: effective riparian buffer zones have two to three vegetation zones, with a mix of smaller shrubs and larger trees.

- Determine ideal size: the width you choose is highly dependent on the function of the buffer, e.g., bank stability (5 metres), sediment removal (10–30 metres) and wildlife corridor habitat (10–300 metres).

Potential for salt/de-icing/snow removal damage

Spray-salt damage is most evident along heavily travelled highways where high speeds result in a high volume of salt spray being deposited on nearby plants and trees. Damage is typically most severe within 18 metres of the road, although it can sometimes extend much farther (for example: spray deposited on elevated highways over trails). Consider the following to minimize the potential for damage:

- A minimum distance of 5 metres from the roadside can reduce the stress of salt on trees. This is dependent on the grade; a downward slope towards the tree will increase exposure to salt damage. It is crucial to plant salt-tolerant species in these areas.

- Water trees well in warmer winter temperatures to lower the concentration of salt in soil.

- Avoid locations that are highly trafficked by snow-removal operations. If your trail is plowed in winter, keep in mind that deposited snow piles can crush young saplings.

Accessibility

A tree’s shape can impact a site location’s accessibility, therefore:

- Consider the growth form of the tree: Will lower branches obstruct pedestrian traffic? Will a dense crown or branches obstruct sightlines and affect pedestrian safety and vehicular traffic?

- The trail corridor must be maintained for accessibility and safety; trail corridors are discussed further in Planting Distances.

6. Root considerations

Tree roots serve multiple functions: they anchor the tree to the ground, absorb water and nutrients, and store food reserves. Root growth, development, size, form and function are controlled by genetics, environment and management. The roots of most trees develop in the top one metre of soil, with most of the small absorbing roots located in the top 15 centimetres of soil.

Potential for root issues during transplanting

- Roots are easily torn and damaged during the transplanting process, especially small, fibrous roots.

- Girdling roots can circle and create congested root systems, drastically limiting the lifespan of a tree. When planting, be sure to check that roots are not circling, and have the potential to expand outwards.

- Girdling roots are often associated with planting too deeply, compacted soil and poor nursery practices.

Root zone requirements

Biomass aboveground does not equal biomass belowground.

- Planting holes should be wide and long, not deep. Never dig a hole deeper than the root ball.

- Roots may extend laterally for large distances, often 2-3x the width of the crown.

Root conflicts

- Roots are opportunistic and will grow where conditions are favourable (water, air, nutrients). Some species have more aggressive root systems than others. If possible, remove competing plants from the area.

- Mature trees may have roots that extend underneath a trail. When planting adjacent to a trail, consider a tree species with a taproot rather than one with shallow roots or one that is prone to surface roots. Keep in mind that mature trees may develop surface roots over time, especially when conditions are poor.

7. Potential impact of invasive species

An invasive species has a destructive impact on one or all of the following: built infrastructure, natural assets, and/or human health and safety. An invasive species often lacks natural enemies or other forms of competition to keep its range and population in check.

Integrated Pest Management is a holistic approach to prevent and manage pest damage, and keep pest populations below specific thresholds. A combination of preventative practices and carefully selected control strategies and treatments are used, with an emphasis on reducing pesticide use.

The threshold of pest populations that triggers pest management varies and is species-specific. Pests and invasive species that have severe human health impacts, such as giant hogweed, may be treated with zero tolerance while other pests that are simply a nuisance may be treated with a higher level of tolerance. Early detection and action are critical to an effective response.

A long-term strategy for most invasive species includes the following:

- Dispose of invasive plants in garbage, not compost. Discarded flowers may produce seeds.

- Remove the most prolific seed producers first (identify the fruit-bearing plants in late fall).

- Dedicate a certain time of each year to control efforts.

- Plan to replant native species once the invasive species have been eradicated.

- Follow-up monitoring is crucial to remove seedlings that may come up after initial removal efforts.

Anyone using a pesticide, herbicide, fungicide, etc., is responsible for complying with all federal and provincial legislation regarding its use.

Resources for invasive species vary by region. The Invasive Species Centre is a great resource that highlights common invasive species and management strategies.

The Government of Canada’s Invasive Alien Species Strategy provides information about the prevention of new invasions, early detection of new invaders, rapid response to new invaders and management approaches.

8. Pests and diseases

Plant selection, site preparation and monitoring young plants can help to manage many pests and diseases. Refer to local nurseries to help to identify and manage common pests and diseases. Trees are resilient, and the presence of a pest population may be within a manageable threshold for the tree (e.g., insect feeding and leaf-distorting pests and diseases). Pests and diseases will continue to change over time with climate change, warmer winters not leading to dieback of insects, and pest/disease migration through regions. Trees with potential pests and disease issues are noted in the companion tree list. To learn more about the pests and diseases impacting trees in Canada, refer to Natural Resource Canada’s online tree list – available here.